Memorial Day- Its black roots

54th Massachusetts Infantry in Boston, 1863

Memorial Day is upon us and so are the memories of parades, American flags, flowers, cookouts with family and friends, and a three day weekend. In the midst of COVID-19, some Memorial Day traditions will remain memories. Of note, however, is that Memorial Day, also referred to as Decoration Day, is grounded in tradition and, most importantly, Decoration Day has black roots.

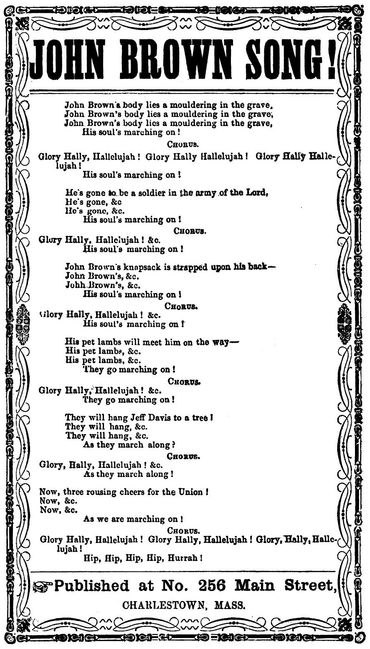

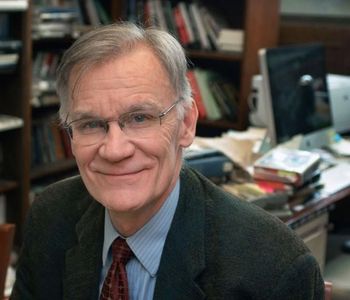

The first nationally recognized Memorial Day was held at Arlington National Cemetery on May 30, 1868, but the “First Decoration Day” was held three years earlier in 1865 at the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club in Charleston, South Carolina. Earlier in the Civil War, the club was made into a Confederate controlled prison that housed over 260 Union troops who by 1865 had tragically died from exposure and disease. Preceding the fall of the City of Charleston, Confederate troops quickly buried these soldiers in a mass grave behind the stands before fleeing the city, leaving behind huge numbers of newly freed slaves. David Blight, a professor of American History at Yale University, in his groundbreaking research noted the immediate humanitarian efforts of the newly freed slaves: “One of the first things those emancipated men and women did was to give the fallen Union prisoners a proper burial. They exhumed the mass grave and reinterred the bodies in a new cemetery with a tall whitewashed fence inscribed with the words: ‘Martyrs of the Race Course’… then on May 1, 1865, something even more extraordinary happened… a crowd of 10,000 people, mostly freed slaves with some white missionaries, staged a parade around the race track. Three thousand black schoolchildren carried bouquets of flowers and sang ‘John Brown’s Body.’ Members of the famed 54th Massachusetts and other black Union regiments were in attendance and performed double-time marches. Black ministers recited verses from the Bible.”[1] Following this historic event, the African American dominated crowd took part in what is now viewed as common Memorial Day traditions. In addition to the parade, “they enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches, and watched soldiers drill.”[2]

African American children gathering in front of the American flag

Washington Race Course & Jockey Club

Charleston, South Carolina

This historic view of Memorial Day is an amazing one and one that is not well known both inside and outside of the African American community. Also, other HistoryMakers have shared their Memorial Day or Decoration Day memories. Hairstylist James Harris (1948 - ) recalled that on “Memorial Day, you spent together… the holidays was always spent in a family cluster at most picnics, we always went to a place called City Point, [there] was a beach where there was a bandstand… And the black people sat around the bandstand because that's where the trees were. Then you would cross the road, and it was nothing but sand and the beach, and that's where the white people were. They suntanned and we chilled.”[3] Federal Appellate Court Judge Ann Claire Williams (1949 - ) had similar memories in Detroit centered on a family picnic: “I remember Memorial Day… we would get up about 4 or 4:30 in the morning and go to one of the beautiful parks in the suburban areas. And you know it was a first come-first serve basis, so we'd get up really early and I would go with my cousin and her family… we would go save the site and we would get a big site with four or five picnic tables and have everything ready.”[4]

The late Chicago educator Frances T. Matlock (1907 - 2002) recalled: “May the 30th, Decoration Day, we called it back in those days… my mother took us to see all of them. We would be leaving home early and get downtown and sit down in front of the Art Institute [of Chicago, Illinois] and sit on the curb and watch until the parade started. We'd be running out there to look and see if the parade started.”[5] Newspaper editor Gale Horton Gay (1954 - ) also described some of her memories of Memorial Day: “... the parade in Mount Vernon [New York] would pass by our block. And, I remember… hearing the bands coming down the street and thinking, Oh, I gotta get outside the parade's coming, you know. But, it would pass right in front of the house… and, you know, your friends are playing in the band…”[6] But not all memories were pleasant. Famed actor Robert Guillaume (1927 - 2017) noted one memory of the Memorial Day parade in St. Louis, Missouri: "a group of white guys would get into a fire truck and come through our neighborhoods, and their idea of fun was to throw garbage from those trucks at us--at the kids who might be following the truck."[7]

Arnold Stancell with his mother and her friend at Pelham Park in the Bronx on Memorial Day

David Blight

David Blight

David Blight

So during this COVID-19 Memorial Day weekend, as you celebrate, think of how historian David Blight so aptly characterized newly freed African Americans and the holding of the nation’s first Decoration Day: “By their labor, their words, their songs, and their solemn parade of flowers and marching feet on their former owners’ race course, they created for themselves, and for us, the Independence Day of the Second American Revolution.”[8

David Blight

David Blight

[1] David Roos, “One of the Earliest Memorial Day Ceremonies Was Held by Freed Slaves.” History.com. May 15, 2020.[2] David W. Blight, “The First Decoration Day.” Zinn Education Project, 2011.[3] James Harris (The HistoryMakers A2007.241), interviewed by Adrienne Jones, August 28, 2007, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 15, James Harris remembers family holidays.[4] The Honorable Ann Claire Williams (The HistoryMakers A2000.042), interviewed by Julieanna L. Richardson, June 20, 2000, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 8, Ann Williams shares cherished family memories.[5] Frances T. Matlock (The HistoryMakers A2002.083), interviewed by Larry Crowe, June 3, 2002, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 10, Frances T. Matlock remembers meeting a stranger at the Decoration Day parade in Chicago, Illinois.[6] Gale Horton Gay (The HistoryMakers A2006.172), interviewed by Denise Gines, December 14, 2006, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 1, story 13, Gale Horton Gay describes the sounds, smells, and sights of her childhood.[7] Robert Guillaume (The HistoryMakers A2005.114), interviewed by Larry Crowe, April 29, 2005, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 7, Robert Guillaume recalls racist incidents from his childhood in St. Louis.[8] Blight.

ASALH Manasota

Manasota ASALH branch is located in the Bradenton Sarasota area. ASALH mission is to promote, research, preserve, interpret and disseminate information about Black life history and culture. Branch meetings of Manasota ASALH, attended by members and friends of Sarasota and Bradenton areas, are opportunities to network and to plan for ASALH events. Each meeting begins with a Moment in History, a brief presentation about a key point in local, national, or historic African American History. These presentations enrich our knowledge base and help to deepen the connection between Manasota ASALH and the Manatee and Sarasota community.

Copyright © 2026 ASALH Manasota - All Rights Reserved.

Manasota ASALH, Inc. is a 501c3 non-profit.